Tice Cin spoke to the co-founder of the award-winning theatre company on authenticity, Black British mental health, the everyman and their place in his work.

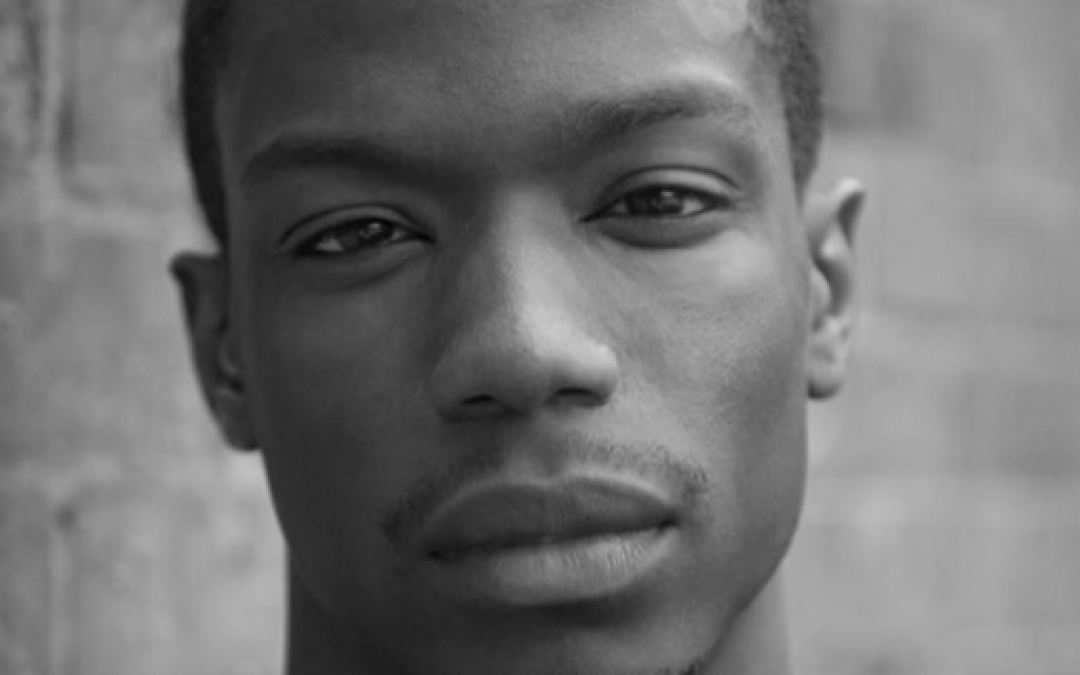

Ryan Calais Cameron is a writer, director, actor and producer from Lewisham. With Shivani Cameron, he’s the co-founder of Nouveau Riché, a multi-award winning theatre company who have always done things differently. Their objective has remained focused on nurturing and bringing unique stories to the foreground. Nouveau Riché’s reputation has grown rapidly since, going from self-funding the critically acclaimed Queen of Sheba in Camden for a week, to winning an Untapped Award at Underbelly Edinburgh Fringe in 2018. There they sold out, won the Stage Award and a year later in August 2019 performed Typical in Edinburgh. Queens of Sheba focused on the rise of misogynoir, based on the DSTRKT Night spot incident of 2015, and Typical on the tragic true-life events of Black British ex-serviceman Christopher Alder.

In April 1998 Christopher Alder was the victim of a brutal murder in police custody; an unlawful killing ensued after he was injured in a fight at a nightclub. In the twenty years since, his campaigners, such as sister Janet Alder, have fought for justice in his name against a system designed to hide such cases. Ryan Calais Cameron’s depiction of Christopher Adler in his Typical – directed by Anastasia Osei-Kuffour – is expansive, thorough and deeply incisive, investigating the way that British society stereotypes Black masculinity and the racism that is embedded into the system.

Typical was first performed in August 2019 at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and then at the Soho Theatre in London for four weeks in December. Then the Nouveau Riché team performed, directed and filmed a new version during the pandemic’s lockdown, which is now available to watch on the streaming service, Soho Theatre On Demand.

What characterises Calais Cameron’s play is the way that his everyman emphasis on Christopher Alder tells us his story in a way we haven’t seen. Blackwood brings us the character of Christopher Alder, who oozes music and bounce. In a poetic script, circling around the refrain ‘typical’ (“waking up hungover, but there was no night before, typical“) we see him eavesdropping on his neighbours, making cheeky comments about their unspiced food, and setting out to ‘bogle with the night while the night is still young’, whilst he’s still young. Sometimes, his eyes turn to you and you’re there with him in a way that feels intrinsically theatrical. The rhythm of his voice is familiar and playful, ‘put book back where I took book from’ and there are some moments that could have been taken right out of one of Blackwood’s iconic stand-up sets – anecdotes about family and more. The music and styling firmly plants us in the late 90s, we know where we are and even the jokes that glitter through the early scenes are of their time, friends go together like ‘batty and bench’ and his friend Joe (who looks ‘like he shops in Baby Gap’) has apparently slept with the Spice Girls. Alcohol, neon lights, club culture. This could have been another play, but amidst everything we are shown racially charged aggressions throughout. The bouncer won’t host him (‘won’t host my humour’). A white woman fetishises him. Europop starts to sound insidious. Music cuts and light bowls out of shot. What follows is a painful demonstration of police brutality, held in motion through Blackwood’s poignant portrayal.

I spoke to Ryan about Typical, authenticity, Black British mental health, the everyman, and the inner-workings of the award-winning theatre company

~~~

Tice Cin: How have you found it navigating the industry? Did you have a mentor or anything?

Ryan Calais Cameron: A lot of things were just trial and error. Before we even had a company, it was more just a collective of minds. A couple of people who were like, ‘Yo, we think the same and want the same kind of things, we should start owning our work’. You can make people money for the rest of your life and never be rich; that’s so weird to me. I was wondering ‘How are other people in this industry eating, because it doesn’t make sense to me?’. Everybody always tells us that there’s no money in theatre but there must be, there are people that are eating massive. Those people are the producers.

It was about getting the right content and then when we put on our first show, Queens of Sheba, it was noticing the legal things we needed to do and then I got a part-time producer run with S, which helped with funding and stuff. I just learnt. Being an artistic director, I need to understand who I’m employing, what they’re doing and what’s the right amount to pay them. I worked as close with the producer as possible to understand everything she was doing, and to see what areas we needed to build. It helped me know what needed to go where. Learning on the job. Even stuff like taking my own contract as an actor, when it came to contracting actors for Nouveau Riché I looked at my own to learn how to contract people and how much they needed to be paid.

Same with my writing. Learning about governance, all that kind of stuff. There were people like New Diorama, Underbelly, Omnibus who I was contacting. Camden People’s Theatre who sometimes I’d get them on the end of the call and ask questions like ‘How do I get a business account?’, ‘How do I register as a company?’. They were pointing me in the right direction. We built relationships with those companies when we first started working on our shows and started R&Ds and stuff. A lot of people took interest in us because we were just some kids from South doing some madness. They were like ‘You guys can do this’. Even with New Diorama, the way that they sensed it could be a massive show when we felt like we were just playing around. For me, it was having those conversations with people and considering who was really about it for us and who really cared. The relationships were built on them seeing something in us. Trust too.

TC: You mentioned previously that Typical emphasises the private life of an everyman character. How do you find writing interiority and the private life of a character, and then representing that on stage or on screen?

RCC: I’ve always seen it. I can watch any show from now or in the last twenty years with an all white cast or white protagonist and I would never watch it and think I needed to turn it off because it was an all white show that I wasn’t able to understand, that I don’t identify with these white characters. I watch it and see that there are themes that these people go through as human beings that I can identify. It made me think how come whenever we see Black people on stage there are people who say they’re never going to get it because it’s a ‘Black thing’. Black people are also human, funnily enough. That was my main trigger to go ‘This is a character’, just like any other man. Also, what I wanted to look at is: what actually separates us? At what point does a man become a Black man, and at what point does a Black man graduate to just being a man? Is that ever possible? In the comfort of your home, you don’t really have to think about your race. You don’t have to think about how you look towards the world, you’re just yourself.

With Typical, thought is shown through it being a one-man play. From the beginning of the piece I have to set up the rules. From the first scene I let people know. In this world, the fourth wall is broken and anything he is thinking or feeling is going to come straight out to us. An agreement that I set up with the audience straight away so that it doesn’t feel weird as it happens throughout the piece. We’ve been doing this for the last hour. . .

TC: What was the filming process like?

RCC: Anastasia, the director, and I discussed, ‘How do we create a hybrid between film and theatre?’ So we started off by asking, ‘What is it we love so much about theatre?’. The intimacy. We were going, ‘Okay, we can’t have people right up in the screen so how do we get that feeling that you are there?’. Right with him. By his face. By his side. Having all those cameras gave us the freedom to capture those moments that were more intimate that you would naturally get in a theatre. How do we make a theatrical experience to watch at home?

TC: Do you think that you’re going to carry on in this vein of hybrid theatre or perhaps move more into film?

RCC: My company Nouveau Riché produced this and at the moment we’re very much experimental film and theatre based. In terms of my freelance work, I tend to do more TV. With Typical, that’s something the majority of productions are going to have to do. We don’t know what’s around the corner. I want to be known for doing something and doing it well. I first want people to trust us to bring them good experimental theatre. We’ve found an art form that we’re excelling in; let’s continue to expand on that first.

TC: You guys got started the quickest post-lockdown right?

RCC: Right out the blocks! We were one of the first to get back. I think we were the first company to get back straight into the room, we didn’t have anyone else to go by and learnt on the go. Imagine this was right after lockdown, the first time I’d left my house in two months or something. You have to remember; this is when we didn’t know anything about Covid. Every half an hour it was *disinfectant spray*. Half of the team had to be on Zoom and that felt weird. A lot of experimentation. These are the things you’ve got to do to continue to tell your stories. That innovation. Initially we were going to do a tour and nobody was thinking of filming anything. Then go forward and we didn’t want to let the pandemic stop us from doing something.

TC: In terms of creative ownership, how do you feel about opening up your projects to adaptation in other mediums?

RCC: This year is the first year that’s happened because we’re quite fresh still to other companies wanting to adapt our work. At the moment, where everything that we’ve done is still so fresh, I’m not going to allow anything to leave the company. It’s like having a Spiderman reboot while the other is still new. In the future, it is going to feel weird because there’s so much integrity that’s put into our work. Yes I would let someone do a version of Queens of Sheba or Typical but there would have to be a serious conversation first to see if it’s coming from a place of hype, or a place of meaning and sentiment.

TC: What are your key focuses when you write about community?

RCC: That people are included and the stories are authentic. There are things I could compromise on but the one thing I won’t is the authenticity of the story. I need somebody from that world or community to watch that show and say ‘Yeah, that’s it’. First and foremost. I think this is something that a lot of artists struggle with because the way the industry is set up is that the question is often, ‘This is cool but are white people going to be able to get on this?’. That’s always the initial kind of response from organisations: ‘If white people don’t like it, then we aren’t gonna sell’. The thing is, white people are people. Trust me, they’ll like stuff that’s entertaining. Let’s just be authentic to the people and world from which this comes from.

TC: I’ve noticed that you’re quite research-led as a writer, for example when you write outside of your own field of reference.

RCC: When I wrote Retrograde, that was set in New York and over a year’s worth of research. I hadn’t been to New York and I had to make it look like I’d lived there. The most nerve-wracking thing is when my agent sent it out to New York and I’m just sitting there like ‘ooo’, probably the most nervy I’d been in my life thinking about the Americans reading it and saying ‘We don’t speak like that’.

In Queens of Sheba I did so much research and it still wasn’t good enough, so I brought on another writer to write with me to get it authentic. It took so much weight off my shoulders because I didn’t realise how much I needed that. I had mad writer’s block but I didn’t know what it was. I wanted to write something that was 100% pure but what I was beginning to write was a Black man’s version of a Black woman’s experience. As soon as I got another writer on board, the words felt so pure. Seeing the backend of that and how Black women then responded to the play. . . I said to myself, ‘We did something good today’. There’s no way I would have been able to do that. There’s only so much research you can do on something that’s happening right now and bringing Jessica L. Hagan on board, she was able to give her lived experience to the piece. I can’t heavily research something that’s happening to somebody right now. That’s why the piece is banging.

TC: I saw this interview of yours where you were saying you worked with the same people you started with. How are you finding that experience of building your team up?

RCC: It’s the best! People say to me, ‘What do you think of this or that happening in the industry?’ and I don’t know because it doesn’t happen here [at Nouveau Riché]. If I want to work with an artist, then we get money and bring them on board. Putting that team together for Typical to be filmed was incredible. One of the things that helped us oddly, was the fact that everybody was out of work in our industry at that moment. We were calling up the editor from Game of Thrones. We got the guy doing sound from Harry Potter. It’s an incredible team that we were able to put together. The best thing about it was the safety of the space, I knew that there wouldn’t be any madness because we don’t play that. It was that experience of going, we’re all coming to do what we want, in a safe space and we’re going to make something that we all care about. It should just be like that on every project. We’re so fortunate to tell our stories in such a way; it should be the best experience of your life everyday.

TC: It’s true. A lot of the old boy companies will tell those pitching that they want to build a team that’s tried and tested, which seems to be code for ‘We want somebody who we have been working with for the last thirty years’. That tried and tested is not necessarily what we need right now.

RCC: Exactly. Getting in people who are passionate. If people aren’t tried and tested, how are they ever supposed to get that experience then if you’re always using the same people? It’s a way of keeping other people out. The company that I’ve been able to work with over the last five years, we’re now very experienced. The work that we do outside of Nouveau Riché, those people can’t say we’re not experienced. With Nouveau Riché, I now have four and a half years of experience being an artistic director. That’s what we try and do. If them man are not gonna give you that experience then let’s pull together everyone from our community that’s passionate and wants this, and let’s begin to move.

TC: How do you engage with unfamiliar people who approach your company to work with you?

RCC: I need to know who you are and why you want to get involved. Hype and clout are wonderful things to look at but they don’t mean anything to me, I want to know where your heart is. I find it really interesting when someone hollers at us and says that they want to do something. We’ve had good and bad. Jessica Mensa who assistant directed on Typical and Queens of Sheba, she just hollered at me and said she was really passionate about getting into the arts and saw what we did and wanted to get involved, and if anything comes up to get in touch with her. I thought, ‘That’s sick, we’re putting her on something’.

There are some people who’ve said they wanted to work with us but then when we’ve got to negotiations what they’re offering is ridiculous and it becomes clear: no they don’t want to work with us, they want to try and exploit us. It’s for me as the leader of the organisation to look at those situations and interrogate them.

TC: Sometimes you don’t even know what the shape of the exploitation is until a few years pass and you see it from hindsight.

RCC: Exactly. As long as you learn from it.

TC: What’s one of the main industry things that you wish you’d known when you first started out?

RCC: How to negotiate a deal and have an understanding of how contracts work. I think that’s something that keeps a lot of young companies out, or losing out on a lot: not knowing their worth. I learnt. I took one bad deal and then thought, hold on a second, ‘If he made this much, that doesn’t make sense’. So I thought to myself I won’t do that next time. Everything we’ve learnt has been learnt on the job. I’ve pushed certain things and wondered what happens if we ask for certain amounts or if we say that we’ll take something on the backend.

Over the years I’ve seen the value of theatre makers and how much they are devalued and undervalued in the industry. I’m just trying to restore that. That’s been my thing, realising ‘Actually you guys can’t really make this without us’ and there should be some more respect. If I’d never made anything before or the last three productions had been one star productions then I’d understand that it’s potentially weird for me to come in the room with my chest high, just bossing everybody. I’d have to be humble. But when you know the work is good then you have to be able to be treated a certain way, you’re not just a cheap option and the work does what it needs to do.

TC: Could you tell me a little more about the casting process for Typical?

RCC: We auditioned quite a lot for Typical to be honest. We had a casting director and brought in a lot of people. The main difficulty was the subject matter and what we were asking the person to do. I wrote a piece that would force an artist to come out of their comfort zone fully in terms of the stamina and endurance that they would need to hold something like this. You have to remember that this is a whole entire production on the shoulders of one man. I could see it in a lot of people that were auditioning that they just weren’t ready yet. You have to think about how many Black artists have been given an opportunity like that before to be that type of leading man.

There was a difficulty finding actors who could do both light and shade. I needed somebody who could be 100% comedic and bring us into the story, and then also 100% dramatic who could take us through the story. We found a lot of really good actors who could do the drama but the comedy was really difficult. Again, we haven’t been given those everyman roles that could draw audiences in like that. We saw lots of people until Anastasia suggested Richard Blackwood on the last day of casting. I thought, ‘Let’s try that, we might be able to do it’. We were lacking somebody that had that aura and could really pull an audience in with their charm and charisma, and Richard does that naturally. He’s been doing stand-up for over twenty years so that’s what he does, he goes onto a stage and commands that room. We brought him in and he was flying out to do another project on that same morning so we all came in at like 8am. When we saw him, I was just as inspired by the conversation after the audition and how much this story played a massive part to him – where his heart was. We made up our minds like an hour later.

TC: It feels important to have that dynamism of light and shade, and not play it straight throughout because people can become desensitised to what they’re seeing.

RCC: If people do not care about the protagonist, then we don’t have a story. We see things happen to Black men every single day, the thing that makes you care is the human in it. I was talking to somebody yesterday and I was saying we speak about George Floyd a lot, I think the world seemed to have discovered racism in 2020 and it’s like ‘No, the reason why you reacted that way is because the video was long enough for you to hear him cry and plead, and hear him beg for his mother, and that was the first time that you guys actually went his guy is a human like us, an actual human being’. Essentially that’s what we do in this piece. This man is not just a tragic story – he is a full three-dimensional human being that you relate to for the best part of an hour. So now what? There’s no excuse, there’s no ‘Oh he might have been this, he might have been that’. No, you were with him and journeying with him from beginning to end. It brings up a lot of interesting questions as you can imagine.

TC: Building safeguarding and awareness into sets – especially for those such as this with these trigger points and traumatic narrative – is increasingly important. I see you had a specialist drama therapist on set, Waybria King. What was that experience like?

RCC: It’s crazy. It makes you think, how comes we’ve never done this before? How comes we’ve not had this on every single production? We need to build this into our budgets. The thing is, with your body and your mind it doesn’t know that you’re acting and you’re going through this experience every single day, having no outlet and going home to chill with your family. We don’t need to bring that energy back home. Richard had Waybria working with him while he was on set for every take. We as a company had a few sessions at the backend. Which was. . . whew. We’d built a relationship with her over the course of the process.

It’s interesting because the majority of the people in the crew were Black, and out of that 80% maybe only 5% had spoken to a therapist before. It’s something in our community that has always been frowned upon. To be that vulnerable, it was a lot. It has to be the way forward because it’s a lot to deal with. Preserving people’s mental health and just making sure that you’re alright so that you don’t spiral into anywhere, so that you never feel you’re alone. I feel like the industry is so rapid where there are fifteen things to think about at house, you’ve got to make sure this person’s ok, make sure your script is ok and check in with the director – through this you need someone with the actors who are there, asking ‘How are you doing?’ to show people they’re not just a pawn in this, they matter, and they’re a human being aside from all of this.

TC: How’s your acting going? Are you thinking of working on any projects soon?

RCC: I might do, but it’s just not been on my mind. I started writing and producing at the same time and there’s so much artistic freedom there. When I was acting I was so frustrated and the majority of things I would say to people all the time is ‘someone needs to write something like this’ or ‘why isn’t anyone producing something like this?’. It would get me angry all the time. So when I started writing I was like great I can write the stories I wanna write and put on the people I want to put on, when I started producing I was like great, I don’t have to wait for nobody at all! I get a bit anxious when I think about acting and having to audition and wait on people. It’s a weird thing to go back to. I think if I did act it would probably be in stuff that we do.

TC: I see that you’re one of the three new associates at The Albany. That’s amazing. Have you any idea of where that work will lead?

RCC: We’re going to do some great stuff there. I’m from Nouveau Riché which is a small company, so it will be interesting to work with a bigger space and budget. Angela Clerkin and arts collective Initiative.dkf are on board as well so it’s exciting. They’ve got three venues, do you know what I mean? Canada Water Theatre. The Deptford Lounge. Then I’ve got a massive imagination so I’m looking forward to us experimenting more with music, live performance and filmed performance. When I first spoke to them I asked them, ‘How do you guys feel about making The Albany the most exciting theatre in the country?’. And now we’re gonna try and do a ting.

It’s complicated with Covid, knowing when to do stuff and how to hold things. I was talking to someone the other day about producing and unproducing. ‘Unproducing’ is a new technique that producers have had to learn now, when your show is going up and you have to be able to pull everything apart. It’s difficult. One of the other difficult things is knowing that despite needing to make money, I didn’t imagine some plays off-stage. When you write something you envision where it’s going to be and I don’t really want a B or C version of it. I have to hold off. Every decision has to make sense. Some things I didn’t write for an audio-drama or to be received online, I wrote it for an audience to be in there. With Queens of Sheba there was a buzz, it’s an experience, as well as story you can come out like you’ve come out of a concert. That’s what I want to do with shows, I want to bring you lot to a concert. We’ll see, by God’s grace we’ll be able to get back in these rooms.

~~~

Watch Typical on:

https://sohotheatreondemand.com/show/typical

Support Nouveau Riché’s trailblazing endeavours and follow their journey here: https://www.nvrch.com/

Author

Tice Cin is a writer and music producer, currently working on digital art at Barbican as part of Design Yourself collective. She shares news of her work on Instagram and Twitter.