K Redking shares his meditation on the Afro-Carribean roots and fruits of soundsystem culture.

On a tour of Jamaica in March this year, Prince William gave a speech expressing his “profound sorrow” over slavery which “should never have happened”—but never explicitly apologised or owned up on behalf of the Royal Family, nor acknowledged their part in this dark stain on Britain’s history. In Belize, protests by local residents in advance of “The Cambridges” forced them to cancel their visit. This island-hopping holiday, funded (of course) by the UK taxpayer (as always), was widely seen as a charm offensive: using the royals’ soft-focus power to dissuade other Caribbean nations from taking the same path as Barbados. In November last year Barbados diplomatically dumped the Queen as their head of state, declared themselves a republic, and gleefully made Rihanna their chosen Bajan icon.

Disentangling a nation state from the clutches of Empire is a messy and complex business, with a supermajority referendum often the required exit ticket. But the momentum across the Caribbean colonies has been building for years, refueled in part by the recent waves of Black Lives Matter consciousness-raising actions.

One of the tricks of Empire is to imbue a sense of belonging in its subjects, once the unpleasantries of a violent takeover have been finished, by homogenising the language, culture, media, and social mores in the colony to that of the parent state.

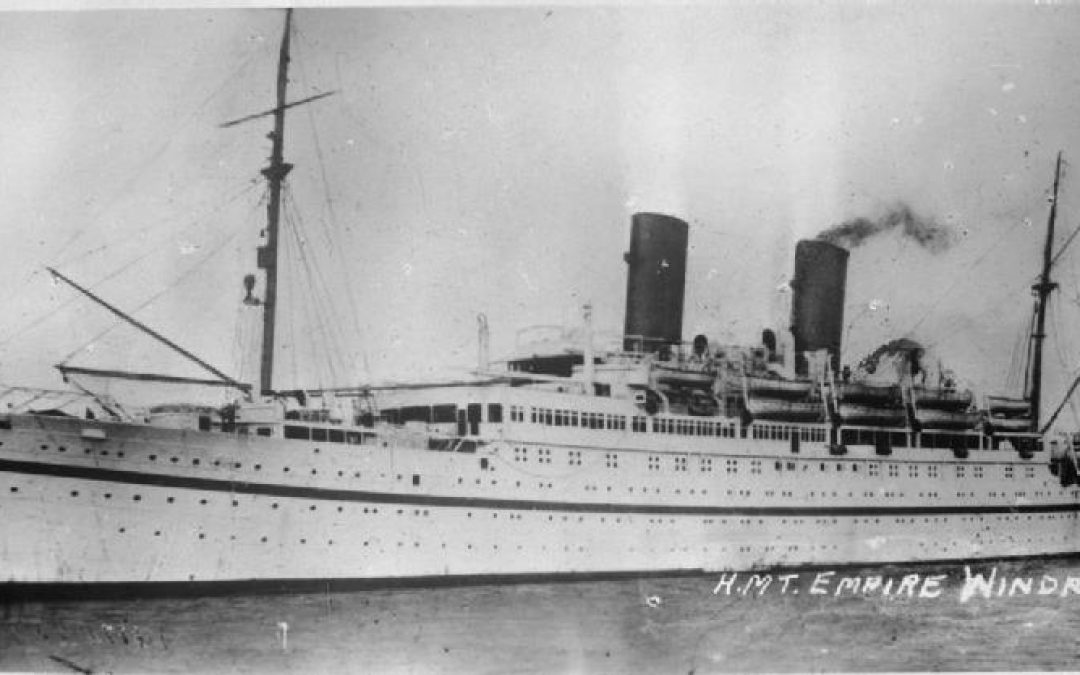

The Empire Windrush

In the aftermath of WWII, the state bizarrely (in the context of what had come before) chose to extend citizenship to all colonial subjects of the Commonwealth, with the British Nationality Act of 1948, giving them equal rights to UK-born residents. This precipitated the arrival of the Windrush generation from the Caribbean, before Official Britain realised that they weren’t exactly keen on actually treating these Black colonials as equals. The Act was eventually watered down in response to the blatant racism from the wider White society. When the colonials came here expecting parity to their masters, that was a bridge too far. Immigration controls were tightened up, the door slammed back shut.

And yet – the door had been opened up long enough for something positive and life-affirming to happen. The colonials brought their own music and culture with them – including sound systems – and they weren’t about to sit quietly at home watching Auntie every evening. Like most immigrant communities, initially they tended to live and socialise together, and slowly became integrated with wider society over time, but not without much anxiety.

Babylon, 1980

This tension (unbearable at times) is documented in the 1980 film “Babylon”, directed by Franco Rosso, and still available on DVD. The story follows the ups and downs of a sound system crew, scrimping to beef up their system housed in a Deptford railway arch, battling for domination in the soundclashes, guided by spliffs, and excellently scored by Dennis Bovell (who was jailed himself for spurious offenses with his own Sufferer’s Hi-Fi rig). The crew must endure racism from the police, the threat of fascist boneheads ganging up on them, and aggravation from locals in Edward Place. The neighbours might have reasonably had a point about the late-night noise facing onto their estate, but with their backs up, launch into racist tirades and threats of violence.

The sound system culture that the film captures is entirely Caribbean. The selectors, DJs, operators, participants—there are few white faces. There is a very difficult-to-watch scene in Babylon where their one white friend, Ronnie, is assaulted, as the frustrations and anger of one of the crew, Beefy, boil over and are misdirected at him. The sound system culture in Babylon seems so far removed from the rest of the city around it, operating in a seemingly parallel universe. It is almost inconceivable to imagine it having authority approval in any scenario.

The film’s eventual denouement feels a little bit forced, and out of character – but the underlying message that the Black community can only take so much more of this shit, both from wider society and Official Britain, before the powderkeg explodes, is abundantly clear. The rage from this intolerance (and other incidents like the New Cross fire) culminated in the 1981 riots.

Jumping forward more than 40 years in time to today brings some light to this darkness. Official Britain – and you can include who you like in that nebulous definition, from the police, to the Royal Family, military institutions, the apparatus of the State, etc. – still drags its heels, speaks out of the corner of its mouth, and regularly “others” black and marginalised communities. No truth and reconciliation commission here. But White British society more generally has slowly come to terms with and acceptance of multiracial communities.

As evidence of this, as part of the Mayor’s Borough of Culture, with high quality printed colour maps encouraging people to follow the “sound system trail” near Deptford High Street, Lewisham Council joyfully celebrated this part of London’s culture. Britain’s culture. The crowds that came on a dry summer day, the weekend before the Jubilee celebrations, were young and old, black and white, straight and queer. Wider British society having accommodated itself to a new tradition, brought in by “outsiders”. Time and space leading to gradual acceptance – it is after all essentially music and dancing in the outdoors, with drink and food. What better way to break bread with your community?

Dennis Bovell & friends in the Albany Garden

Dennis Bovell’s sound system is by far the loudest. Situated in the garden of the Albany Theatre – which is thanked in the credits of Babylon, and itself a target of fascist attacks in the late 70s – there is a no man’s land between the speaker stacks and the front of the crowd, where only a few brave individuals dare to enter. Even with earplugs in, it is incredibly overwhelming, and when any bassline kicks in, it’s enough to rattle the fillings out of your teeth. It’s here, despite the volume, where the age profile of the crowd is widest, with toothless toddlers running around the feet of toothless Rastafari pensioners. It has a relaxed, community vibe to it, with people hugging each other, catching up with others possibly not seen in real life for a few years, and trying their best to have conversations a bit further back from the wall of sound.

Unit 137 soundsystem in Deptford Market Yard

Unit 137 occupy a space in the corner of Deptford Market Yard, playing a mixture of upbeat dubstep, jungle, and dub to a younger crowd. Their beautifully designed and brightly painted orange rigs add an artistic touch to the proceedings. In a delicious schadenfreudic irony, one of the rigs is pointed in the direction of one notorious resident’s flat, who complained repeatedly to Lewisham Council about the noise emanating from one of the arches when Aaja Music had their studio there. The music from Unit 137 is far louder than anything ever to come out of Aaja. You have to wonder if Lewisham didn’t do this on purpose.

Lemon Lounge

The WWFM x Lemon Lounge system is crammed into a small yard at the entrance to Creekside Artworks, playing a mix of global dance tunes. Just around the corner from local mainstay pub The Birds Nest – not featured in Babylon, but probably unchanged since 1980 – one Deptford resident tells me that “they’ll never be allowed to do this here again” as he points up to the scaffolding protecting the venue from the construction of flats next door. The issue of development and gentrification naturally comes up in conversation throughout the day; and of course like any other inner London area, the Brixton and Deptford captured in Babylon are markedly different today. But the development at 1 Creekside is not for luxury flats, as most people assume. The whole block has been acquired by Lewisham Council from the developer, 40% for social rent and 60% for shared ownership. So maybe there is hope that events like this will be able to continue here in the future.

The crowd for the Deptford Queer Soundsystem Day

Finally the best party of the day is up at the river at the Master Shipwright’s house, where a long queue has formed from mid-afternoon along the old stone boundary wall. Gideon’s R3 soundsystem were active pre-lockdown with their anti-Trump and pro-Remain party/marches through the centre of London, driven by deep house music. The conscious messaging of R3 is in direct contrast to the vacuous actions of the “Save Our Scene” grouping and Homebass sound system, whose anti-vax and anti-lockdown protest raves, during a Covid pandemic’s wave, aligned themselves firmly with the politics of the hard right wing of the Conservative Party CRG group. R3’s return to the streets is eagerly awaited. For this event they paired up with Turner Prize winners the Black Obsidian Sound System, who are still on a high after their recent sold-out voguing extravaganza in the Crofton Park Rivoli Ballroom; and whose mission is to reach out to and empower black and queer communities.

DJs Gideon and OK Williams

The crowd is the most diverse of the day, with Adonis favourites Shay Malt and Hannah Holland bringing the rapture of house music to a spectrum of skin colours and sexualities dancing in the gardens. It is this “Deptford Queer Soundsystem Day” event that offers a glimpse into the future of what a sound system could do. Combatting LGBTQphobia and racism at a grassroots level through dancing together, listening to uplifting music promoting peace and understanding, tolerating difference, accommodating shifts in society, towards a more harmonious place for all of us to live together.

This event was the subject of now-deleted derogatory comments on the We Are Lewisham Facebook pages, saying that the R3/BOSS system wasn’t really a sound system at all, with other contributors making veiled homophobic remarks. If there is discrimination and intolerance being preached at the top of society then this will inevitably continue to permeate through society. The apologies for the injustices of colonialism from the State may never come. But it is events like these, with music and dancing providing joy and togetherness for communities at a local level, that progress and acceptance will take place. Lewisham Council should be applauded for their ongoing amplification of black and minority voices through the arts; and for scheduling and promoting this wonderful event as part of their programme for the year.